Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Caitlin Eichner, Shapell Roster Researcher.

After several years working on the Shapell Manuscript Foundation’s “Roster of Jews in the Service of the Union and Confederate Armies and Navies, 1861-1865,” we have come across a LOT of names. A handful of the names stick, and can be recalled at will; but most do not, and remind us how thankful we are that the database and our email server have a key word search function. We record our favorite discoveries in weekly reports so we can easily revisit stories we have learned. Building the narratives for literally thousands of men rewards the soul, but tests the memory.

We look into men who came from all walks of life. Men who were born all over the world, and served from all over the country. We find connections between a few soldiers here and there; brothers, cousins, neighbors, comrades, friends. But, it’s rare that we see a name come up consistently across large numbers of different soldiers’ records, except maybe references to “Mr. Lincoln.” So translator Charles Newburgh stuck out in our memories.

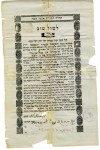

One of the best resources when researching Union* soldiers are the pension records of Civil War veterans held by The National Archives. The contents of a Union pension application file vary greatly, depending on who was applying, and what type of claim they were making. Veterans could apply for benefits based on disabilities created by injury and disease incurred during the War, or later benefits based on soldier’s advanced age. Widows, under-age children, and dependent parents could apply for benefits following a soldier/veteran’s death. Age, degree of disability, and relationship to a soldier are typical facts to be proven in these different types of applications. The Bureau of Pensions therefore routinely collected evidence about a soldier’s birth, marriage, and death during an investigation into a claim. These are the three hallmarks we hope to find in a pension file, because they provide the strongest and likeliest connections for us to confirm a soldier’s identity or verify that a soldier was Jewish. Was the guy buried in a Jewish cemetery? Married by a Rabbi? Did his birth get recorded in the local synagogue’s records? Gosh, we hope so!

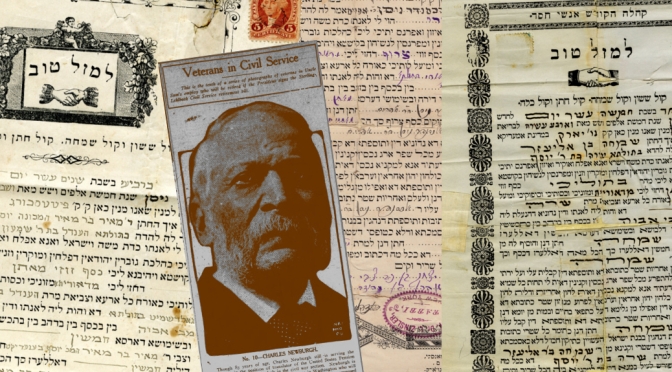

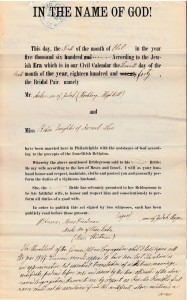

Because so many Union soldiers were immigrants, and some returned to their homelands after the war; many of the documents they submitted were written in foreign languages, typically without any translation. The Bureau of Pensions therefore needed translators to decipher these records, so the claims could be processed. We come across the names of many different translators when reviewing said documents in pension files—translators in German, Italian, Portuguese, etc.—but only one when we gleefully stumble on documents in Hebrew. A Mr. Charles Newburgh. The Hebrew translator has become an old friend, a favored guest in our research. For every ketubah, every synagogue birth record we’ve found, submitted from the late 1880’s up until the early 1920’s, Newburgh is there. Helping our Jewish soldiers prove the details of their lives so they could receive crucial benefits, and helping us put together the specifics of these soldiers’ lives more than a century later.

Charles Newburgh played such a key role in our searching, that we began wondering who he was, and whether he might have kept records of the translations he did at the Bureau pf Pensions. If anyone would have had the inside track on which Union soldiers were Jewish, it would have been Newburgh. Could he have been one of Simon Wolf’s sources for his 1895 roster?

But, with so many soldiers to track and deep understanding of the mess that is digging though administrative agencies’ back logs, an investigation into Charles Newburgh’s background was put on hold. That is, until we came across Charles Newburgh in a place we hadn’t expected.

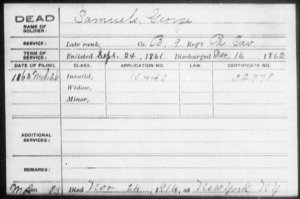

Otto Zoeller served as a Private in the 7th NY Infantry; and was included in Simon Wolf’s book.

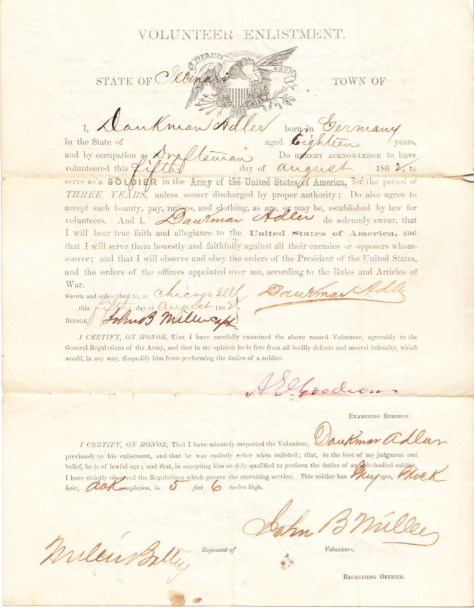

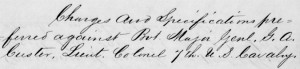

Since Wolf employed the 19th century acceptable practice of “name profiling” in compiling his roster, we independently authenticate each and every name, including Private Zoeller. The pension record indexes showed that the soldier Otto Zoeller had actually served under an alias, and that his true name was CHARLES NEWBURGH. That coupled with the fact that this soldier died in Washington DC, in 1930, after the period we had observed our translator operating, set off alarm bells.

![Pension Record Index for Charles Newburgh, Alias Otto Zoeller[7]](https://primarysourcehistory.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/zoeller-ottz_3307_177.jpg?w=150&h=93)

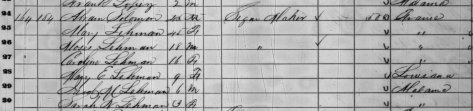

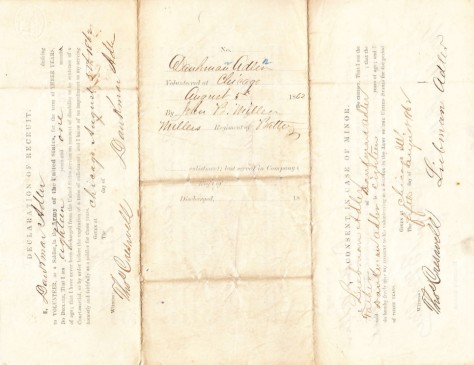

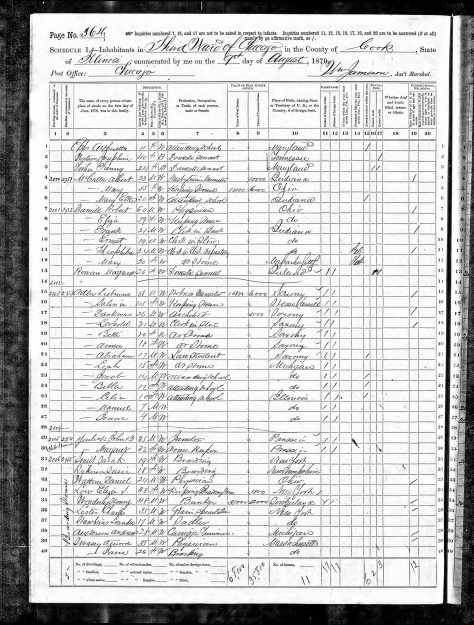

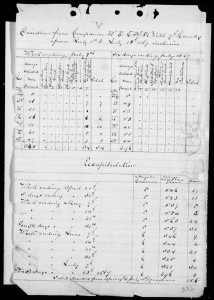

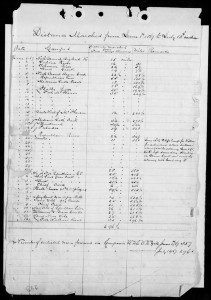

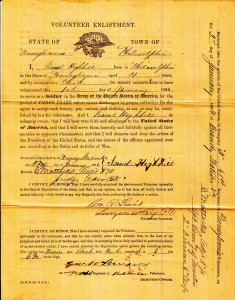

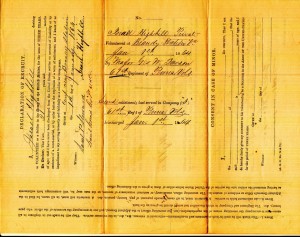

Charles Newburgh was born in Oettingen, Bavaria, Germany on April 27, 1837. He came to America by way of Liverpool, England, on the S. S. City of Philadelphia in 1854, and settled in New York City prior to the war. Newburgh became an American citizen in 1860, and so answered his new country’s call to arms almost exactly a year later; enlisting in the 7th NY Infantry for 18 months under the name Otto Zoeller. He was wounded in action at the Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1, 1862, in Henrico County, VA; receiving a gunshot wound in his left arm. Due to this injury, Newburgh was discharged for disability, and his military career was brought to an end.

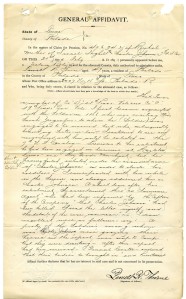

It is unclear why Charles Newburgh served under an alias. We often see soldiers hiding their identities because they were too young to serve, and their families refused to give them permission to join. Newburgh was 21 years old at enlistment though; very comfortably over the age of majority. The affidavit he provided to the Bureau of Pensions provides no explanation. Newburgh simply states he served under this alternate name, likely because he was already an employee in the department, and had no need to prove his identity.

Zoeller is a German name of Bavarian origin, so Newburgh chose a new name from his homeland. Like so many surnames, Zoeller was originally the name of an occupation: a tax collector, or toll gatherer. This was a prominent and lucrative position to hold, so families with this name were often wealthy and well-to-do. Maybe this is why Newburgh chose the name; to add some clout to his persona.

Speculating as to why the soldier chose to use an alias, perhaps it had something to do with his younger brother receiving an appointment as Captain of the 10th NY Infantry six months earlier; while he was a lowly private. Joseph Newburgh, by records showing his age across the years, appears to have been born the year after Charles. He enlisted at the start of the war, and like his brother was wounded in action. Joseph was shot in both the arm and the side at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. When Joseph was discharged for disability, he re-enlisted in the Veteran Reserve Corps.

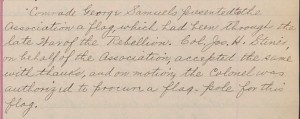

After the war, Joseph Newburgh provided Charles with an affidavit in support of his pension claim; confirming Charles’s identity as Otto Zoeller, and stating that they had run into each other regularly during the war around Newport News and on the Chickahominy River. Joseph even saw Charles the day after Malvern Hill, and observed his wound. A few years later, Charles repaid the favor, and gave an affidavit on behalf of Joseph’s widow, Sophie. Joseph met an unfortunate end on a steamboat named the Sandy Fashion. There was an explosion on board the Sandy Fashion along the Big Sandy River, and Joseph Newburgh drowned. Sophie applied for a widow’s pension, but at the time of her application, a veteran’s death had to be directly related to an injury or condition that occurred or began during and due to his service. Charles gave testimony that prior to the war, based on observations Charles made when the brothers would go bathing in the river, Joseph was “a good swimmer.” After the war, the injuries to his arm had left Joseph “crippled… to such an extent that he could not swim afterwards.” Other passengers of the Sandy Fashion survived the accident, swimming back to shore; but Joseph was unable to do so. The Bureau of Pensions did not agree with the Newburgh family’s assessment that Joseph’s death would not have happened if not for his injuries during his military service, so Sophie’s claim was unfortunately rejected. Joseph’s funeral was held at The Plum Street Temple in Cincinnati, OH; now called the Isaac M. Wise Temple, built for the famous rabbi’s congregation.

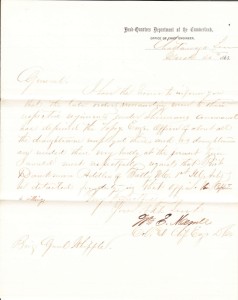

Charles Newburgh led a much longer, less tragic life after the Civil War than his brother. He moved around frequently before settling in Beloit, WI for over a decade. There he met and married his wife Kate, and started his family. Then, in 1887, he was hired as a translator by the Bureau of Pensions, moving to Washington, DC, and unknowingly beginning his century-later relationship with our research team. In Washington, the translator was known as Professor Charles Newburgh, although we have not yet found that he ever served on the faculty of any school. He translated Hebrew and German documents for the Bureau, and proved to be not only an expert in languages, but in comparative religions as well. Newburgh gave many lectures around DC, primarily on behalf of the Washington Secular League, discussing, among other things, the origins of different religions’ central texts, and “the philosophy of the Hebrews.”

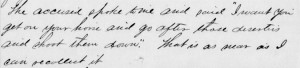

Charles Newburgh’s sharp mind can be readily observed reading the appeals he submitted to his office on behalf of his own pension claim. The Bureau of Pensions held that Newburgh’s injury during the war had not left the veteran “unfit for manual labor” and that he was therefore not entitled to the benefits he claimed. In his appeal, Newburgh analyzed the language of the law under which he filed his claim, and like a skilled litigator, pulled apart its meaning, and explained why the Bureau had misinterpreted the legislative purpose and incorrectly found that he did not qualify:

“As to the law: The act provides ‘That any person who served in the military or naval service of the United States during civil war and received an honorable discharge, and who was wounded in battle or in line of duty and is now unfit for manual labor by reason thereof, or who from diseases or other causes in line of duty resulting in his disability is now unable to perform manual labor, shall be paid the maximum pension under this Act, to wit, thirty dollars per month, without regard to length of service or age.’

This clause of said Act divides claimants into two distinct classes: 1., persons wounded who are by reason of such wounds now unfit for manual labor, and 2., persons who by reason of disability resulting from disease are now unable to perform manual labor.

Webster’s Dictionary defines unfit by ‘not fit; not suitable.’ For instance, a lame horse is not fit, not suitable to be driven, but may nevertheless be made to pull a buggy or a cart.

Unable is defined by the same authority by ‘not able; not having sufficient strength, means, knowledge, skill or the like; impotent, weak; helpless; incapable.’ A horse unable to pull a buggy or a cart is a very different description and expression from unfit for such work. What the Act contemplates and the distinction intended by it is expressed in perfectly plain words.”

Newburgh argued, based on this understanding of the language of the law, that the fact that the Bureau found that he could still perform some physical acts, in spite of his wounded left arm, did not mean he was suitable for physical labor. His injury did leave him unfit to do much physical work. The special examiner in Newburgh’s case did concede that he put forth a compelling argument, but held the standard intended for receiving benefits under this act was closer to what Newburgh defined as unable; regardless of what wording was chosen and what Webster’s said. Years later, Commissioner of Pensions Winfield Scott would help push through Newburgh’s claim at a rate of $90 a month, after the latter had exceeded the age of 80 and was entitled to hefty age-based benefits.

Charles Newburgh served in the Bureau of Pensions over 30 years before retiring; helping countless veterans prove their claims. He died January 26, 1930, in Washington, DC, and was interred at the historic Glenwood Cemetery. His good works continue to be a boon to the Shapell Roster Project, and we are thrilled that now we get to celebrate both his military and administrative service, so hopefully others too remember the name “Charles Newburgh.”

*Pension records also exist for Confederate soldiers, but are more difficult to track down because they were submitted at the state level to the former Confederate states, and are therefore not centrally held in one place. To find a Confederate soldier’s pension application, if he even submitted for one, you must know not only the regiment he served in, but also where he lived after the war; because these veterans would submit for benefits in the state they were living in at that time, which was not necessarily where they were living when they enlisted.

Interested in staying updated with the latest research news and discoveries? You can follow the research team’s progress as it’s made at the Shapell Manuscript Foundation Facebook Page and Roster Project Album, or by following @ShapellManu on Twitter, #ShapellRoster, or check back at our blog for more interviews and news from the archives.

_________________

[1] Department of the Interior. Bureau of Pensions. (1849 – 1930). Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Widows and Other Dependents of Civil War Veterans, ca. 1861 – ca. 1910. Record Group 15: Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, 1773 – 2007. National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

[2]Ibid.

[3]Ibid.

[4]Ibid.

[5]Ibid.

[6]Ibid.

[7] Microfilm Publication T289: Organization Index to Pension Files of Veterans Who Served Between 1861 and 1900. Record Group 15: Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, 1773 – 2007. National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives Building, Washington, DC. In fold3.com (online database). Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2011-2012.

[8] Department of the Interior. Bureau of Pensions. (1849 – 1930). Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Veterans Who Served in the Army and Navy Mainly in the Civil War and the War with Spain (“Civil War and Later Survivors’ Certificates”): Nos. SC 9,487 – 999,999, 1861 – 1934. Record Group 15: Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, 1773 – 2007. National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

[9] U.S. Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992 (Indexed in World Archives Project). Original data: Selected U.S. Naturalization Records. National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives Building, Washington, DC. In: Ancestry.com (online database). Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2010.

[10] Microfilm Publication M1372: Passport Applications, 1795-1905. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, 1763 – 2002. National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives Building, Washington, DC. In fold3.com (online database). Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations Inc., 2011-2012.

[11] War Department. The Adjutant General’s Office. n.d. Carded Records Showing Military Service of Soldiers Who Fought in Volunteer Organizations During the American Civil War, compiled 1890 – 1912, documenting the period 1861 – 1866. Record Group 94: Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1762 – 1984. National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

[12] Department of the Interior. Bureau of Pensions. (1849 – 1930). Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Veterans Who Served in the Army and Navy Mainly in the Civil War and the War with Spain (“Civil War and Later Survivors’ Certificates”): Nos. SC 9,487 – 999,999, 1861 – 1934. Record Group 15: Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, 1773 – 2007. National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

[13]Ibid.

[14]Ibid.

[15] “Deaths.” The Cincinnati Enquirer. Vol. XXXVI. No. 99. April 9, 1878. p. 5. Accessed on Newspapers.com.

[16] The Washington Post. No. 13,785. March 7, 1914. p. 5. Accessed on Newspapers.com. AND “Origin of Bibles Debate.” Evening Star. No. 18,639. October 9, 1911. p. 9. Accessed on GenealogyBank.com.

[17] Department of the Interior. Bureau of Pensions. (1849 – 1930). Case Files of Approved Pension Applications of Veterans Who Served in the Army and Navy Mainly in the Civil War and the War with Spain (“Civil War and Later Survivors’ Certificates”): Nos. SC 9,487 – 999,999, 1861 – 1934. Record Group 15: Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, 1773 – 2007. National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

[18]Ibid.

[19] “Veterans in Civil Service.” The Washington Herald. No. 4952. May 20, 1920. p. 12. Accessed on Newspapers.com.

[20] Courtesy, Brian Tosko Bello.

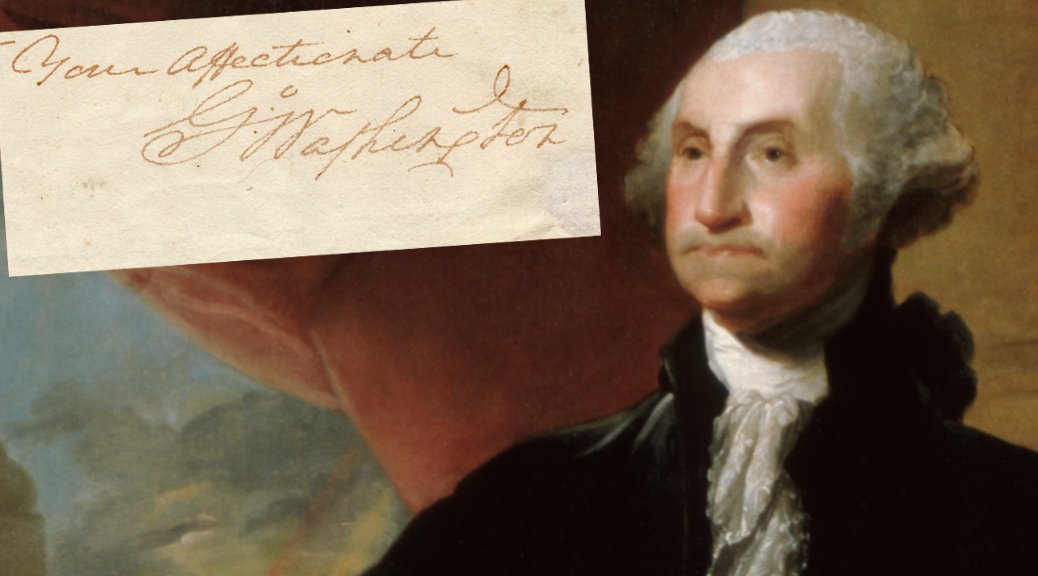

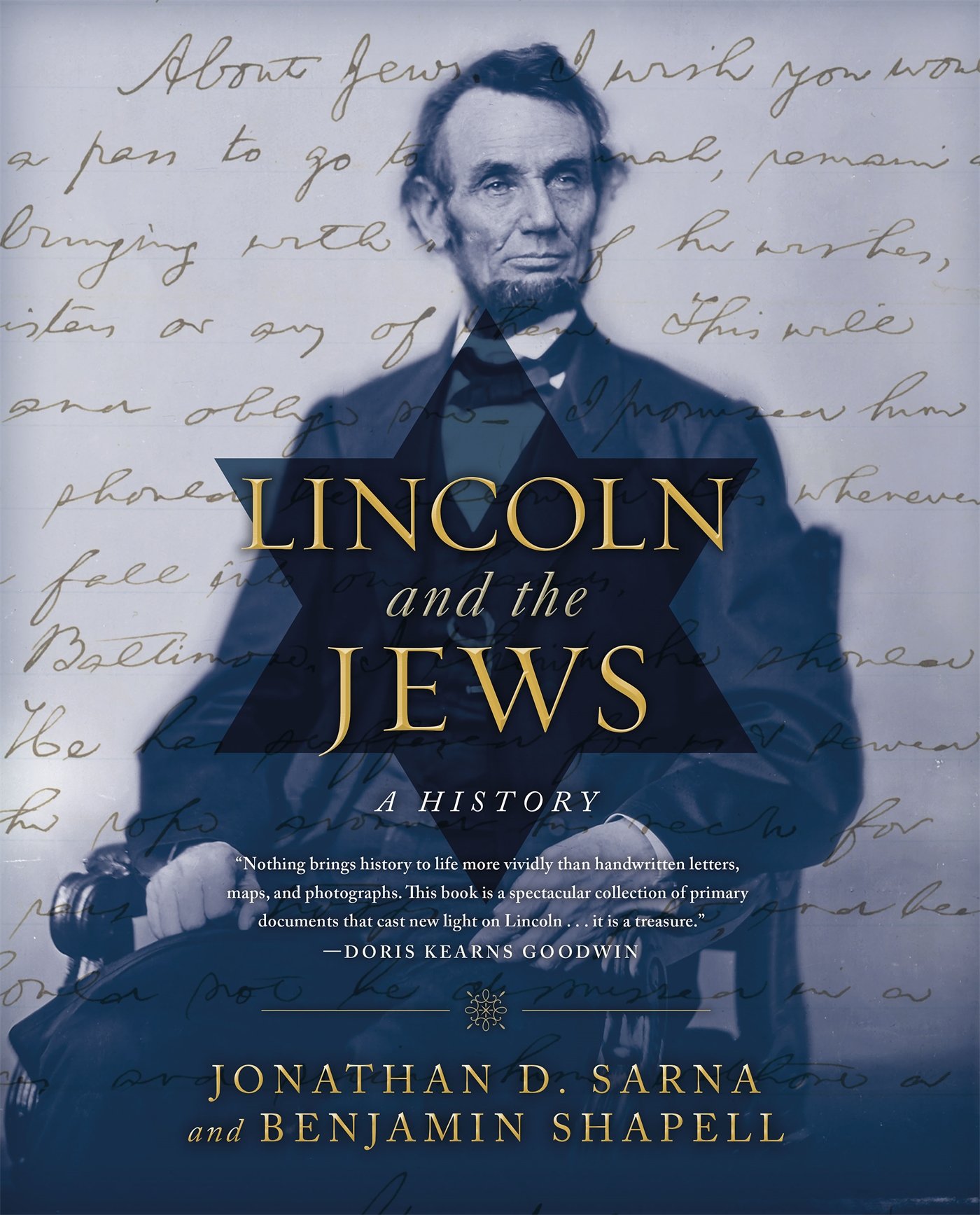

Lincoln and the Jews, by Jonathan D. Sarna and Benjamin Shapell, is an important book on many levels. First, it is a beautiful book, and very very classy. The illustrations, while not rivaling Michelangelo, are copies of historical ephemera: letters, photographs, newspaper articles and related items. Many are priceless because they are written in Abraham Lincoln’s own hand. The others are important because they are personal connections to Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln and the Jews, by Jonathan D. Sarna and Benjamin Shapell, is an important book on many levels. First, it is a beautiful book, and very very classy. The illustrations, while not rivaling Michelangelo, are copies of historical ephemera: letters, photographs, newspaper articles and related items. Many are priceless because they are written in Abraham Lincoln’s own hand. The others are important because they are personal connections to Abraham Lincoln.