Writing about any aspect of the Jewish-Arab conflict inevitably exposes the writer to charges of political leanings. While historians strive for objectivity, the readers of a blog typically are also interested in the blogger’s personal perspective. I hope that this post, and others I write, will inspire you to go learn more about a topic; to challenge my ideas, and be challenged by them in turn.

***

Where should a discussion of the 1929 Hebron attack against the Jews begin? I find it often useful to focus on individuals who trigger change and shape events.

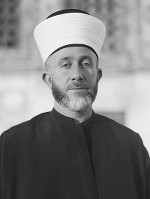

In 1921, Haj Amin al-Husseini was appointed Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, and he rallied Arab nationalism against nascent Zionism. In 1924, the Moslem Wakf began shedding doubt on the Jewish connection to the Western Wall, and in 1928 the Mufti claimed that the Jews were trying to take control of the mosques on the Temple Mount.

One week before the Hebron Massacre in August, 1929, a demonstration was held by the Jews to affirm their connection to the Western Wall. On Friday, August 23, inflamed by rumors that Jews were planning to attack al-Aqsa Mosque, Arabs attacked Jews in the Old City of Jerusalem. Rioting spread to the cities of Safed and Hebron, which both had a small Jewish minority.

On August 24, Arabs mobs attacked the Jews of Hebron. Armed with axes, knives and iron bars, they screamed “Kill the Jews!” They broke into homes and stabbed and mutilated the Jews they found. The mob included respected Arab merchants who killed their friends, clients, and business associates. Torah scrolls were burned. And while it is often stressed that many Arabs hid their Jewish neighbors, reliable accounts placed the number of such cases at 19.

Here you can read survivor testimonies; more details about the riots can be found here.

Sixty-eight Jews were killed, including a dozen yeshiva students from New York and Chicago; scores were wounded or maimed. Soon after, all of Hebron’s Jews were evacuated by the British authorities. Both Jews and non-Jews across the world were horrified by the massacre. The Shaw Commission was a British enquiry that investigated the riots; here is their description:

“About 9 o’clock on the morning of the 24th of August, Arabs in Hebron made a most ferocious attack on the Jewish ghetto and on isolated Jewish houses lying outside the crowded quarters of the town. More than 60 Jews – including many women and children – were murdered and more than 50 were wounded. This savage attack, of which no condemnation could be too severe, was accompanied by wanton destruction and looting. Jewish synagogues were desecrated, a Jewish hospital, which had provided treatment for Arabs, was attacked and ransacked, and only the exceptional personal courage displayed by Mr. Cafferata – the one British Police Officer in the town – prevented the outbreak from developing into a general massacre of the Jews in Hebron.”

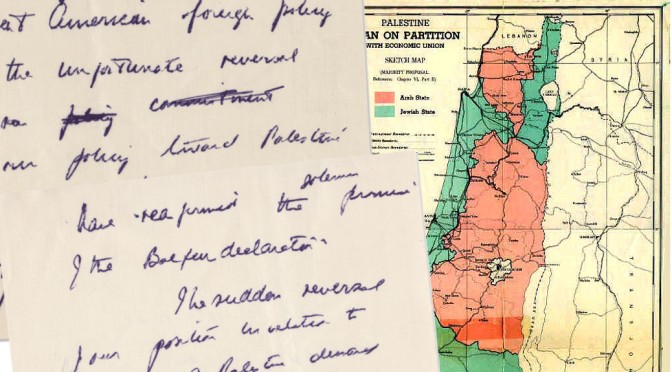

President Hoover sent a message of condolence to the Jewish community; yet his personal correspondence on this matter was much cooler:

“I wish to thank you,” he writes, “for sending your very interesting observations on the situation in Palestine.”

I could end with observations on the shock of Hebron’s Jews who had maintained close relations with their neighbors for many years; on the fallacy of treating the Arab-Israel conflict as political and not theological, or on the obvious falsehood that the root of the conflict is in Israel’s occupation of Arab lands. Yet I prefer to leave you, the reader, to explore this topic, and draw your own conclusions.